Chapter 2 Leonardo’s proportional theory of mankind and the discovery of the problem

Section 1 Leonardo’s “Vitruvian Man” and its “circle” and “square”

Vitruvius used to be a Roman architect and a first century man. During the Renaissance, Vitruvis’ “The Ten Books on Architecture” received widespread interest not only from architects but also from artists in other fields as the only technique book to convey the classical Greek and Roman architectural theory.

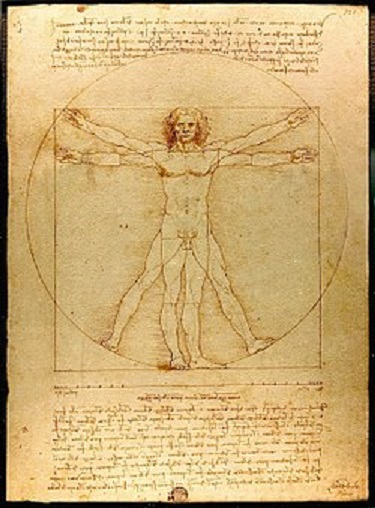

Renaissance artists regarded the description of proportionality of temple architecture written here as the theory of human proportionality in the classical antiquity, and left many works called “Vitruvian Man”. Each was drawn based on the description in Chapter 1 of the 3rd book of this building book, and Leonardo’s “Vitruvian Man” (Fig. II(1)-1), which is owned by the Accademia Gallery of Venice, is most known.

It can be said that Leonardo’s image as a “modern scientist” was formed as the manuscripts preserved in various places of Europe were sequentially published in the 20th century. It has been the subject of quantitative analysis and studies on these quantitative proportional theories include those by Giuseppe Favaro and Rudolf Wittkower. Whereas these studies deal with the proportional relationship of the various parts of the body and the problem of “harmonic proportion” that appears there, Erwin Panofsky’s achievements “Codex Huygens and Leonardo da Vinci’s Theory of Painting” which comprehensively showed Leonardo’s human proportionality study was the beginning in this field.

Renaissance artists believed that the Vitruvian Man’s description contained the norms of ancient Greek beauty, and sought to create a human figure consistent with that description. Specifically, “circles” and “squares” were given and “Vitruvian Man” was drawn. Here the method to drew the “circle” and “square” of Leonardo’s “Vitruvian Man” will be shown through the reference lines drawn in Leonardo’s sketches and the fact based on the geometry which Dr. Mukaigawa found on the first folio of the “Codex Huygens”.

The description of Vitruvius is as follows.

“The structure of the temple is determined by Symmetria. Architects must learn this law carefully enough. This is derived from the Greek proportion called analogia. Proportion means that the limbs and the whole body in every building follow the degree of a certain part, from which the symmetry law is born. Indeed, except for Symmetria or Proportion, that is, unless each limb is correctly assigned to resemble a good-looking human being, no temple can have any means of construction.

Indeed, nature constituted the human body as follows. ---The face is one-tenth from the chin to the hair on the forehead, and the palm is the same amount from the wrist to the tip of the middle finger. The head is 1 / 8th from the chin to the top, 1 / 6th from the top of the chest including the base of the neck to the hairline, and 1/4 from the center of the chest to the top of the top. One third of the height of the face itself extends from under the chin to under the nostril, and the nose is the same amount from under the nostril to the center line of both eyebrows. From this limit line to the hairline, the forehead is also one-third. The legs are 1/6 of the height, the arms are 1/4, and the chest is 1/4. The other limbs also had their own measurement ratios, which the famous painters and sculptors of the past used to garner great endless acclaim.

Similarly, the limbs of the temple must be the most amenable and metrologically responsive to the total size of the individual parts. The center of the human body is naturally the navel. Because if a person spreads his hands and feet and lies on his back, and the tip of the compass is placed on his navel, then by drawing a circle, both hands and toes touch the line. Furthermore, just as a human circle figure is created, a square figure will be found in it. That is, if you measure from the bottom of your foot to the top of your head and the measurement is transferred to your widened hands, you will find the same width and height there, as well as a square plane drawn with a ruler. (the rest is omitted)”

The Vitruvian writings were of great significance to the Renaissance artists who aimed at the reconstruction of the ancient times as a theoretical source. The problem of proportion is often closely related to proportional theory and perspective in architecture. For them, in the tradition of scholarship since the Middle Ages, art was comparable to liberal arts in comparison with the mathematical division quadrivium. The theory of harmonic proportion, which was conveyed from Vitruvius to reproduce the body beauty of ancient Greece, was the norm.

Ventori said: “The Renaissance Italian artists reigned in Europe because they knew how to calculate proportional and perspective effects. Moreover, they made use of the knowledge of the Greek and Roman ancients, not only in their writing, but especially in their modeling work. Many of these relics were of a better quality and were found in Italy than in any other parts of Europe.”

On the other hand, the original description of Vitruvian man is confusing, and, like those of other Renaissance artists, there is controversy over the rationality of its “circle” and “square” explanations, and to the extreme they are just legends. There was an argument that there was no such thing. The background to that was that the studies attempted by mathematicians such as Euler and Cantor did not give a rational explanation. In Leonardo’s “Vitruvian Man” the proportional relationship of each part of the body is said to be closest to the standard value of “Vitruvian Man”.

Leonardo’s “Vitruvian Man”

Leonardo da Vinci’s “Vitruvian Man” is the widely known figure in Figure II(1)-1 and can be called the synonym of Leonardo. This drawing, which should be called the treasure of humankind drawn by Leonardo, is held in the Accademia Gallery of Venice, and makes us feel the harmonized beauty of the well-proportioned human body. According to Ms. Allano, metal brushes, maroon ink, and watercolors were used, and according to Dr. Mukaigawa’s personal opinion, the head, hands, armpits, and legs, which were watercolours, were coloured with brushes. Lines were drawn applying Vitruvian man’s standard to distinguish each part of the human body.

Below the figure of the human body, a straight line is drawn that draws the basic scale with the same maroon ink as the circle and square. The texts shown in the reference material are written above and below this figure. From the perspective of the content, figures, and inscriptions, Leonardo’s idea of “Vitruvian Man” was that he thought of forming a single schema (form, system, framework) on the whole of the paper, centering on the sketch of the human body.

There are two typical reprints, but it seems that there are some problems in the grammatical interpretation. The figure shows the proportions of each part of the body, and how Leonardo himself draws “circles” and “squares”. Below the drawing method is shown, the human body showing the proportional relationship of each part of the body is inscribed in a “circle” and a “square”. The text written below is not a copy of Vitruvius’ description as it is, but shows the proportional relationship of each part of the body based on Leonard’s interpretation, and the proportion of each part of the body drawn on the “Vitruvian Man”. It is meant to explain the relationship. Figure II(1)-7 shows Leonardo’s , which is flipped horizontally and the Leonardo mirror letters are replaced in print. The compositional form of Leonardo’s “Vitruvian Man” can be modeled as a proof form of Euclidean geometry, proposition, special statement, drawing, and proof (Fig. II(1)-8).

Document of Leonardo’s “Vitruvian Man”

Proposition : Architect Vitruvius stated in its architectural theory that the dimensions of human beings are distributed by nature as follows. That is, four fingers become one palm and four palms become one foot. Six palms become one cubito (*) and four heights. Also, the four cubito become a step, and the twenty-four palms become height. And these dimensions are used in his architecture. (* From the tip of the middle finger to the elbow)

Features : If a man opens his both legs so that height is reduced by 1/14 of height and spreads out his arms so that the middle fingers touch the horizontal line of the crown, the center of each tip of the spread limbs is the navel and the gap between the legs is an equilateral triangle.

Drawing and basic scale of “Vitruvian Man”

Drawing : ―――――――――――――――――――――――――――――――

|Finger|Palm|The length of a person’s arms extended|Finger|Palm |

is the same as their height

Proof : From the hair edge to the tip of the chin is 1/10 of the height. The length from the tip of the chin to the crown is one eighth of the height. From the top of the chest to the crown is one sixth of the height. The length from the top of the chest to the hair is one-seventh of the height. From the nipple to the crown is one quarter of the height. The maximum width of the shoulder is one quarter of the height. From the elbow to the tip of the hand is a quarter of the height. From the elbow to the end of the shoulder is one eighth of the height. Entire hand is one tenth of the height.

The position of the genitals is half the height. Feet are one-seventh the height. From the foot to below the knee, it is a quarter of the height. From the knees to the genitals is one quarter of the height. The part from the chin to the nose and the part from the hair to the eyebrows are each equal to the length of the ear and one third of the face.

Regarding Leonardo’s “Vitruvian Man” the Vitruvian man’s criteria described above lead to the fact that the size of the foot is one sixth of the height.

In the figure of Leonardo, lines showing proportionality of each part were written. However, there was a numerical value of 1/7 of the height not written in Vitruvian standard in the description. Moreover, the value is limited to the following text, which is believed to show Leonardo’s own interpretation of Vitruvian Man.

So Leonardo’s description is different from Vitruvian man’s criterion.

Focusing on the reference line drawn in the part “from the upper end of the chest to the hair edge” in these descriptions, it was measured that the position of the navel becomes an approximate value of the “golden ratio” with the big toe of the left foot. Furthermore, when measured in detail, the “golden ratio” can be confirmed on the reference lines written in Leonardo’s ” Vitruvian Man “. What is shown in the following table is the position of the reference line that is the approximate value of the “golden ratio”. When viewed from the navel, which is the center of the “circle” in the figure of “Vitruvian Man”, the positions of these reference lines consist a geometric progression with a common ratio of the golden ratio (1.6180 …… ). The following table shows the geometric progression and the measured values that were the basis of Dr. Mukaigawa’s estimation.

l1 (between umbilicus and nipple) 25.5 mm = k ≒ 7

l2 (umbilical to upper end of chest) 40.5 mm = k × Φ ≒12

l3 (umbilicus to hairline) 66.5 mm = k × Φ × Φ ≒ 19

l4 (radius of circle) 109.5 mm = k × Φ × Φ × Φ ≒ 31

∴ l1 : l2 : l3 : l4 = 1 : Φ : Φ × Φ : Φ × Φ × Φ ≒ 7: 12: 19: 31

The golden ratio is represented by the Greek letter Φ, and the unit length k is between the navel and the nipple.

As is clear from this table, the proportional reference line of Leonardo’s “Vitruvian Man” partially overlaps with the geometric progression of Φ. The sequence is a linear regression sequence (one of which is the Fibonacci sequence described above), that is, the sum of two adjacent numbers is the next number, and the limit value of the ratio of the two adjacent terms converges to a golden ratio.

Until now, it is thought that the difference between the Vitruvian norm and Leonardo’s description was changed from “1/6 of height” to “1/7 of height” because Vitruvian’s ratio of feet was too large. However, if we consider that Leonardo used the elements of the linear regression sequence rather than simply determining the leg length criterion naturally, the statement “1 / 7th of the height” comes from the sequence {2, 5, 7, 12, 19, 31,…}, and a close correlation appears with the geometric sequence of the golden ratio starting from the navel (Fig. II(1)-7).

Therefore, the position of the proportional reference line drawn in the figure is thought to be determined by the “golden ratio” from the measured value of Leonardo’s “Vitruvian Man” and the proportional reference value of each part of the body given by Leonardo himself, written in the lower part of the document. It can be said that Leonardo constructed the picture based on mathematical standards.

Next, let’s talk about the circles and squares of Leonardo’s “ Vitruvian Man”. According to Panofsky, who published a paper that is considered to be the pioneer of the study of the Codex Huygens, the “big circle” in this figure is said to be the “circle” described by Vitruvian man, and Leonardo’s method is cited in that argument. That is, “When both legs are spread at an angle of 60 degrees and the arms that are spread outward are raised by 30 degrees and a posture of an eagle spreading wings is assumed, the big circle contacts the tips of the limbs with the navel as the center”. The description is nothing but the explanation of the statement of the “Vitruvian Man” written by Leonardo. However, Panofsky’s commentary does not explain what geometric method this “circle” was determined by.

When reviewing the geometrical elements drawn on the first folio (Fig.Ⅰ(1)-3) of the Codex Huygens, there was a dotted line with a geometrical meaning that Panofsky did not explain. As mentioned above, Dr. Mukaigawa’s Fig. I(1)-3 is a diagram explaining what this dotted line means. As is said before, the diagonal lengths CG, GF, FE, and EA of the rectangle form the geometric progression of the golden ratio. The big circle of the first folio is a circle whose diameter is AG (2φ) in Reference Fig.I(1)-3. Therefore, the center of this circle is the golden ratio of the center line (unit length 1).

The reader may think that this circle is a circle that passes through the top two points of the center square and is tangent to the bottom side. But that is not the case. When the intercept of the upper side of this circle is calculated (Appendix), it is calculated to be about 0.9550, which is almost 1, and this difference cannot be detected on the figure. The truth cannot be seen unless mathematically rigorous verification is possible. It is necessary to read the meaning of Leonardo’s words, “Don’t let non-mathematicians read my principle” (Windsor 19118r). Leonardo did not explicitly state that he was using the golden ratio.

However, the circle surrounding the human body of Leonardo’s “Vitruvian Man” is actually different from this circle of Vitruvian Man. Because the intercept of the upper side of the square is obviously shorter than the side of the square. Then how did Leonardo decide this circle?

Figure II(1)-10 shows the 81st folio of the Codex Madrid, which Leonardo calculated for the diameter of the “circle” in his “Vitruvian Man”. Explaining in Reference Figure II(1)-10, the larger of the two types of fan shape is a part of the circumscribed circle of the “square” that surrounds the human body, and the height from the base of the square to the apex of the fan shape is the diameter of the circle of Leonard’s “Vitruvian Man”.

Therefore, the “circle” and “square” of Leonard’s “Vitruvian Man” can be described as follows. When drawing a circle that circumscribes and another circle that inscribes a “square”, the circle that touches both of these two circles and also touches the bottom of the “square” is the “circle” of Leonard’s “Vitruvian Man”.

If one considers the square as the Four big Greeks, the “circle” of Leonardo’s “Vitruvian Man” can be described as “the ring that connects the macrocosmos’ universe and the microcosmos’ human body.”

[ Appendix : the length of the intercept ]

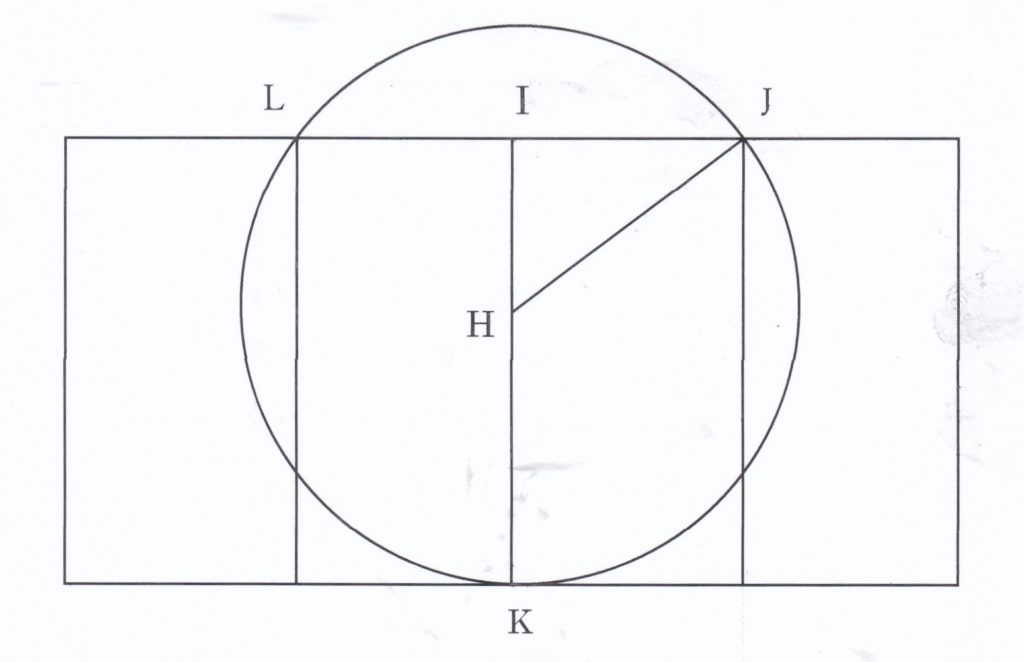

In the diagram above the length of KI is unit and the point of H (naval) divides KI by golden ratio, where

HK= 0.61803…….

The circle the radius of which is HK intersects the upper side of rectangle at the point of L and J.

(HJ)2 = (HI)2 + (IJ)2

Substituting HJ = 0.38196……, it is calculate

IJ = 0.4715……

then

LJ = 0.9550……

Whereas in the case of Leonardo’s “Vitruvian Man”, the length of the same intercept above is calculated as 0.9102…… .

Section 2 Changes in Leonard’s “Vitruvian Man”

German art historian Klaus Irle and painter Klaus Schröer revealed in 1998 that Leonardo was seeking an extremely accurate π based on Leonard’s “Vitruvian Man”. This suggests that the circle of Leonard’s “Vitruvian Man” is not just a circle that encloses the human body, but has a strict mathematical intention.

Leonardo was enthusiastic about seeking circles and squares of equal area, which had been a problem since ancient times, and associated it with drawing the “circle” of his “Vitruvian Man”.

Archimedes cleared that 223/71 < π < 22/7 (that is, 3.140840 …… < π <3.142858 ……) using the relationship between a regular polygon to be inscribed in a circle and that to be circumscribed by the circle about. This method has been followed for 2,000 years since the Greek era.

Leonard wrote in the Windsor folio 12280r, “I make a circle into a square without any doubt.” There are episodes showing that the painter was enthusiastically working on geometrical problems. Leonardo was enthusiastic about this geometry, without almost all his paintbrushes, according to Fra Pietro da Novellara, the deputy of Isabella d’Este, Princess of Mantua, and the abbot of the Carmelites, telling the story of Leonardo’s fate in 1501 (Codex Atlantico 167r-b). Also, in Codex Madrid II-112 face, “At St. Andre’s Night (November 30, 1504), late at night, when the lamp and the paper I wrote are almost running out, I finally found the quadrature of the circle. In the end, I got a conclusion.”

However, there is no way to directly derive “quadrature of a circle” tried also by the great mathematician Gauss, using a compass and a ruler. In 1882, Lindemann proved that π is a transcendental number. It became clear that it was impossible to determine the circle the area of which is equal to that of the square and vice versa other than the approximate value. Leonardo’s description was still within the approximate range.

In the study by Irle and Schröer, the diameter of the “circle” of Leonardo’s “Vitruvian Man” was set to 2φ (1.2168 ……), but Dr. Mukaigawa said that the diameter is (√2 + 1) / 2, that is, 1.2071……. He recognized a geometric progression of the golden ratio on the norm of proportionality of each part of the body of Leonardo’s “Vitruvian Man”, but in order for this geometric progression and the criterion of musical harmony proportionality described by Vitruvius to be established at the same time, we need the value of the diameter (√2 + 1) / 2 of the “circle” given by Leonard. Many geometrical drawings in Codex Atlantico 167r-b etc. are considered to be trial and error for determining this circle.

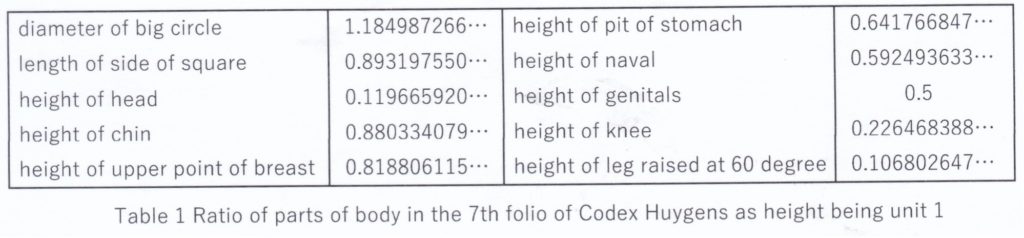

The 7th folio of Codex Huygens is considered to show the transition of Leonard’s study of the composition of human body. It is an example of the evidence that Leonardo tried to draw the human body in the rigorously mathematical form. The drawing process is as shown in the 7th folio, in which a square that encircles the human body with the limbs expanded―→ it is rotated by 45 degrees (at the same time, the apex “a” of the hexagon is determined) ―→ the two points “d” on the lower side of the square are determined ―→ the lower point “a”, which is the apex of the hexagon passing through “d”, is determined- ―→ The highest point and the lowest point of the hexagon are determined, and the outer circle (big circle) of the hexagon is determined.

-1-766x1024.jpg)

A small circle that passes through the lower point of the big circle and touches the upper side of the square is determined, and the height of the human body is determined. The arms raised to the left and right at the height of the head are drawn so that the fingertips are located around the intersection of the square and the big circle. The diameter of this big circle is calculated as 1.1849 ……, where 1 is the side of the square. As Leonard wrote in Codex Atlantico 120r-d “Ask Master Luca about the multiplication of roots”, in order to find the ratio of each part of the body from these geometric forms, it is impossible to calculate such irrational numbers as √2 and √3. It was revealed that Leonardo’s consideration had advanced to such a level.

Table 1 shows the ratio of each part. In the 7th folio of Codex Huygens the human body was not drawn merely with the square or a circle but it was drawn in the rigorously mathematical form based on the square dimension drawn at the beginning.

In the 7th folio various regular polygons are represented and the positions of various parts of the human body are drawn in relation to them. The length of the feet is also different from that of Leonardo’s “Vitruvian Man” and it is understood that Leonardo’s thinking changed from time to time. Although many researchers have explored the age of the Vitruvian Man figures during the Renaissance, Dr. Mukaigawa found that the various regular polygons in Codex Huygens 7th folio have the relation with those inscribed in the circle in the folios from the reverse side of 12th to the right side of 14th of Codex Paris (Fig. II(2)-11 to 14) and Codex Windsor 12542r-v (Fig. II(2)-15). Dr. Mukaigawa pressumes that Leonardo’s original was drawn around from 1490 to 92.

Codex Oxford

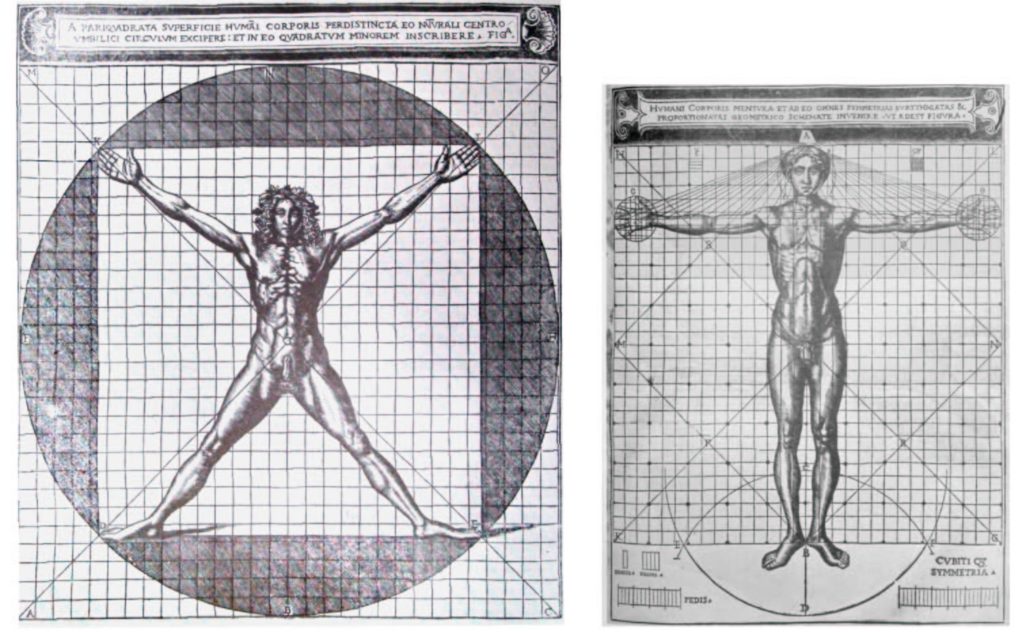

The two drawings of the Christ Church Library collection in Oxford are helpful when considering the drawing process of the 7th folio of Codex Huygens. It is considered that the difference between the “circle” in Leonardo’s “Vitruvian Man” and those of these figures indicates the transition of Leonardo’s thinking. There is a view that the drawings of Codex Oxford play a role of “missing link” that connects the 7th folio of Codex Huygens to Leonardo’s “Vitruvian Man”.

The left arm shown by a straight line extending from the left shoulder to the upper right of the image reaches the upper right corner of the square and the tip of the hand is higher than the top of the head, where the tip of the hand was drawn higher than the cases of Codex Huygens and Leonardo’s “Vitruvian Man”.

The left arm and the legs that are spread out in the same way as that of Codex Huygens 7th folio are drawn as straight lines. The straight line of the widened right leg extends through the navel to the acromion. In the figure, scales are marked on both sides of the body using the length such as cubito, which is a scale based on the length of the arm shown on the lower left of the drawing, and Facio, which is the scale of the palm.

Regarding the big circles in these figures, which Panofsky and Irma Richter referred to as the circles of Vitruvius, Dr. Mukaigawa points out that the diameter of the big circle of the 7th folio of Codex Huygens is 1.1849 …… , and that of Codex Oxford 1.236 …… (=2φ), when the height is unit. There is a very large mathematical paradigm. In other words, Leonard considered distinctly different figures for the size of the Vitruvian circle in the different drawings of these times.

On the contrary, when looking at Fig. II(3)-1 in which Dr. Mukaigawa regulates the 7th folio of Codex Huygens and Codex Oxford to make the “big circles” just the same size, it is understood that the squares have the same size and the same position. Furthermore, from this figure, it can be considered that Codex Oxford was drawn so that the part above the navel was shortened in proportion to the body of the well-proportioned man.

Furthermore, in Codex Oxford, the position of the navel is the point of the golden ratio with respect to the height, and it was drawn in the same way as the first folio of Codex Huygens. That is, the radius of the big circle centered on the navel is √5-1 (= 2φ) with the height being a unit. By comparing these folios, we can see the transition of Leonardo’s way of thinking about the drawing of Vitruvian Man.

The above three drawings should correspond to the three periods of (1) when it was treated as approximate values, (2) when the golden ratio was applied, and (3) when the geometric progression of the golden ratio was performed. In the 7th folio of Codex Huygens various regular polygons were drawn, and the human body was drawn defined by them according to the description method described by Vitruvius, that is, the dimensions described in “Proof” of “Vitruvian Man”. Therefore, each part of the human body was treated as an approximate value. In Codex Oxford, the navel position is at the golden ratio to the height.

In Leonardo’s “Vitruvian Man” each part of the body is defined by musical proportions. As shown in Fig. II(1)-7, each of four terms of the geometric progression of the golden ratios is found in the distances between the three reference lines and the naval and the radius.

It is concluded that Leonardo decided the “circle” as described in Leonardo’s construction method of “Circle” and “Square” in Chapter 2 Section 1 and then in accordance with the law of Double Square’s phyogenesis in the first folio of the Codex Huygens he decided the positions of the naval and the three reference lines of parts of the body forming the geometric series of the four golden ratios based on the radius and then drew the human body at the end.

Leonardo’s “Vitruvian Man” includes the more mathematically significant meaning than the former two, and it was drawn in an elaborate manner.

Section 3 Leonardo and “Vitruvian Man” of Cesare Cesariano version

In the human figure of Codex Oxford “big circle” and “square” are the same as those of Codex Huygens 7th folio, but the human figure of Codex Oxford was redrawn so that the position of the navel divided the height by the golden ratio.

There are pictures of “figure following a circle” (Fig. II(2)-4) and “figure following a square” (Fig. II(2)-5) of the Cesariano version drawn by Paolo Segazone. It is presumed that in the 1490s, Leonardo himself represented the human figure as such independent drawings. Any notice has not been paid to the relation between Leonardo and the Cesariano version of “figure following a circle” because of its poor drawing. It is presumed that a person who was not Leonardo drew it except understanding Leonardo’s intention.

These paintings are thought to show the process of Leonardo’s thinking to the final picture, Leonardo’s “Vitruvian Man” in the Accademia Gallery in Florence.

Figure II(3)-2 is a restoration that Dr. Mukaikawa thinks as the original form of Leonardo’s “Vitruvian Man” drawn based on Figure II(3)-1 shown above, and Leonardo’s thinking process can be inferred. The navel position divides the height by golden ratio, and the hands and feet reach the four corners of the square.

In the “figure following a square” of Fig. II(2)-5, Dr. Mukaikawa examined the intercept length of the arc on the base line. This is an arc whose radius is 1/2 of the length of the side of the square tilted 45 degrees in the center of the figure, and the center of one of them is 1/2 of the radius of the arc apart from the midpoint of the base of the large square of the outer frame along the vertical center line. The other arc is symmetrical about the base line.

Therefore, the intersections of the two arcs, the points E and F in Fig. II(2)-5, are located on the base of the square of the outer frame. The triangles CED and CDF are equilateral triangles. The length of EF is calculated as (√2 × √3) / 4 when the length of the side of the outer frame square is a unit. This value is 0.61237, which is a very good approximation to the golden ratio of 0.61803. Dr. Mukaikawa estimates that Leonardo used this length as the golden ratio for some time.

In order to draw a regular pentagon, it is necessary to obtain a length equivalent to the golden ratio. However, during the Leonardo’s Renaissance, it was not known to draw pentagons using the golden ratio. In Fig. II(2)-13, the same shape as the two arcs at the base of the square in the outer frame of Fig. II(2)-5 is drawn, and it can be seen that Leonardo examined a regular pentagon.

Dr. Mukaikawa believes that most of the “Vitruvian Man” in Vitruvius’ “The Ten Books on Architecture”, which was established in the mid-1500s, was based on the polygons inscribed in the circle of the Codex Huygens 7th folio. Furthermore, he infers that in the 1490s Leonardo drew ” Vitruvian Man” in different icons, such as in Cesariano’s “figure following a circle” and “figure following a square”.

Traditionally, Leonardo’s ” Vitruvian Man” has been interpreted as showing the standard of Vitruvius based on musical harmonic proportion. There is no research except that of Dr. Mukaigawa and the joint research of Klaus Irle and Klaus Schröer in 1998 which captures the “square” and “circle” of Leonardo’s “Vitruvian Man” as geometrical regulatory figures.

Since “square” and “circle” have geometrical meanings and the golden ratio and the geometric progression of the golden ratio included in the Vitruvius’ standard have been clarified, the human body proportion theory represented by Leonardo’s “Vitruvian Man” must be reexamined based on Leonardo’s mathematical knowledge, including its chronology.