Chapter 3 Leonardo’s literal expression and its problem

Section 1 Interpretation of Divina Proportione in Paragone

Divina Proportione in Paragone

The first chapter of the “Codex Urbino” (Codex Urbinas Latinus 1270), which became the original of the book known today as Leonardo’s “Theory of Painting” (Trattato della pittura), discovered by Guglielmo Manzi in Vatican Library is called “Paragone”.

Paragone is known as an indication of Leonardo’s view of art, showing how much painting had an academic foundation when compared to other arts. Here, it will be clarified that the ” divina proportione ” written in Paragone means the golden ratio.

Leonardo’s “Painting Theory” is a practical book like the others, but the existing “Painting Theory” was compiled by his beloved disciple Melzi (1493-1570) after Leonardo’s death. The underlying geometry, the bases of those such as linear perspective, described therein is important for painters who project three-dimensional space onto a two-dimensional screen.

The studies before Dr. Mukaikawa’s research on Leonardo’s “Vitruvian Man” were based on Leonardo’s theory of proportionality as a fractional system based on musical harmonic proportion.

Paragone describes the proportion of a beautiful face, and there is the word ‘divina proportione’, but the adjective ‘divina’ related to this proportion has not been considered in relation to Leonardo’s human proportion.

In Paragone it is stated that “divina proportione” exists in a beautiful appearance, and that appearance has “balanced proportions”. Leonardo was a master of musical instrument lyre, and knew that the harmonic proportion that was the basis of music was the basis of the theory of human body proportion. Therefore the beautiful appearance of “balanced proportions” can be replaced with the “harmonic proportion” of the face. And the description in Paragone has a pure mathematical meaning.

Research of Leonardo’s human proportion

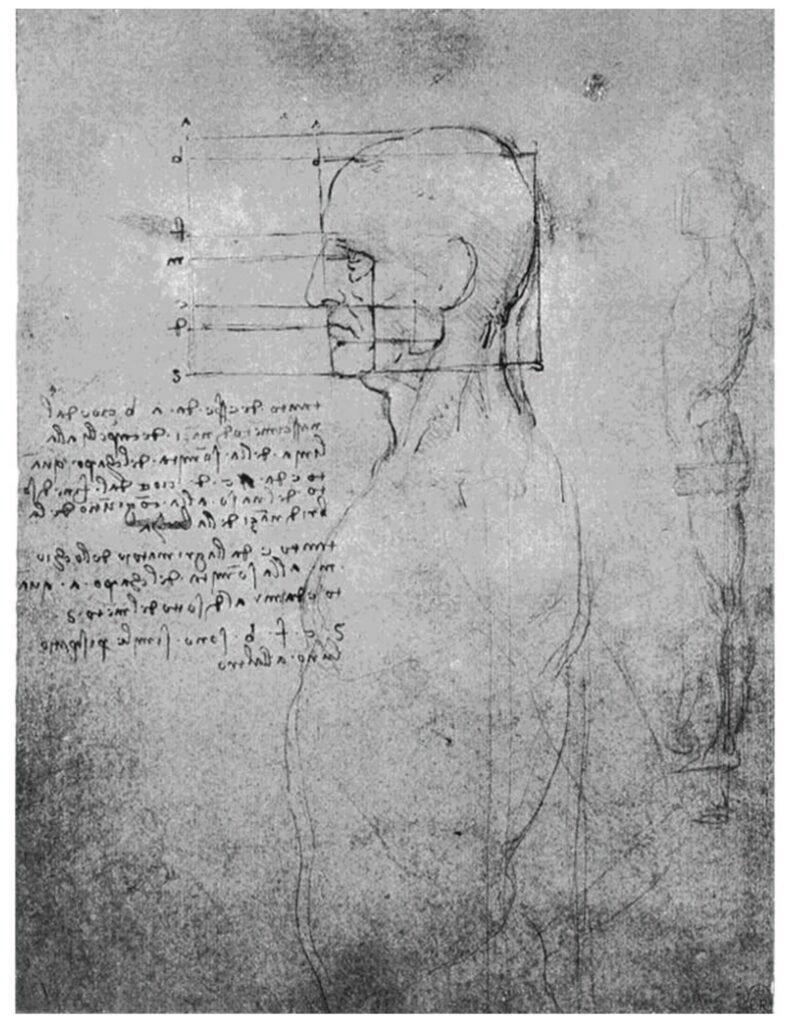

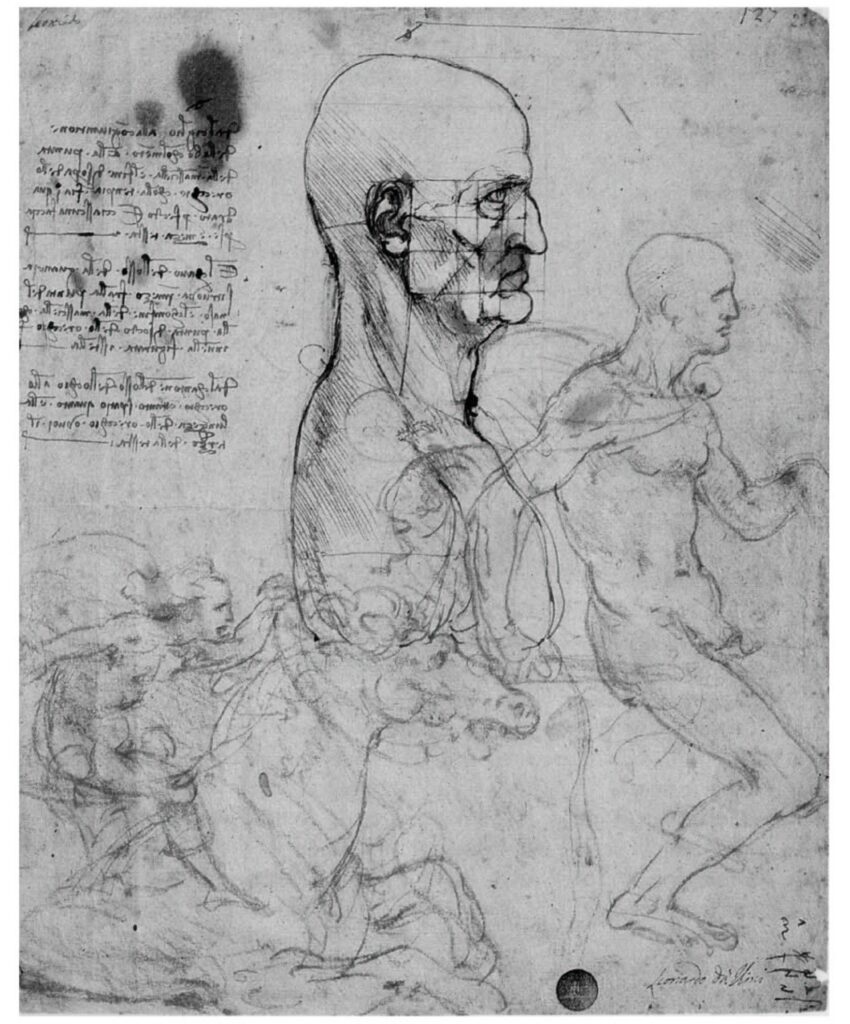

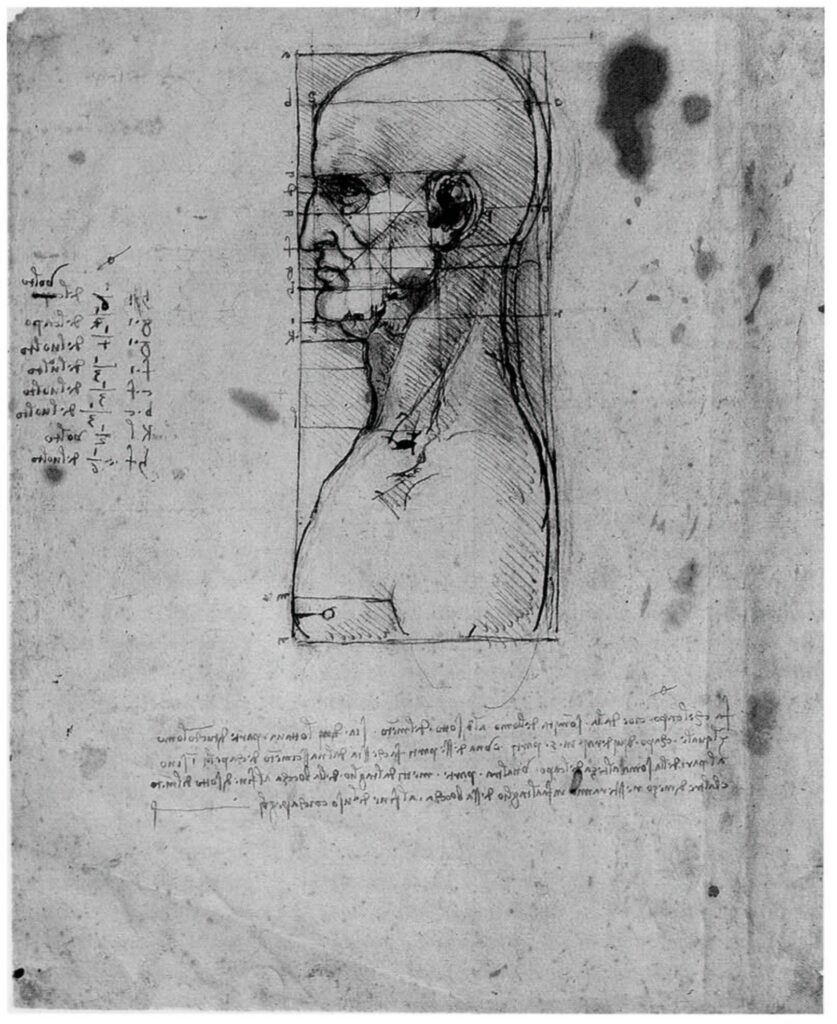

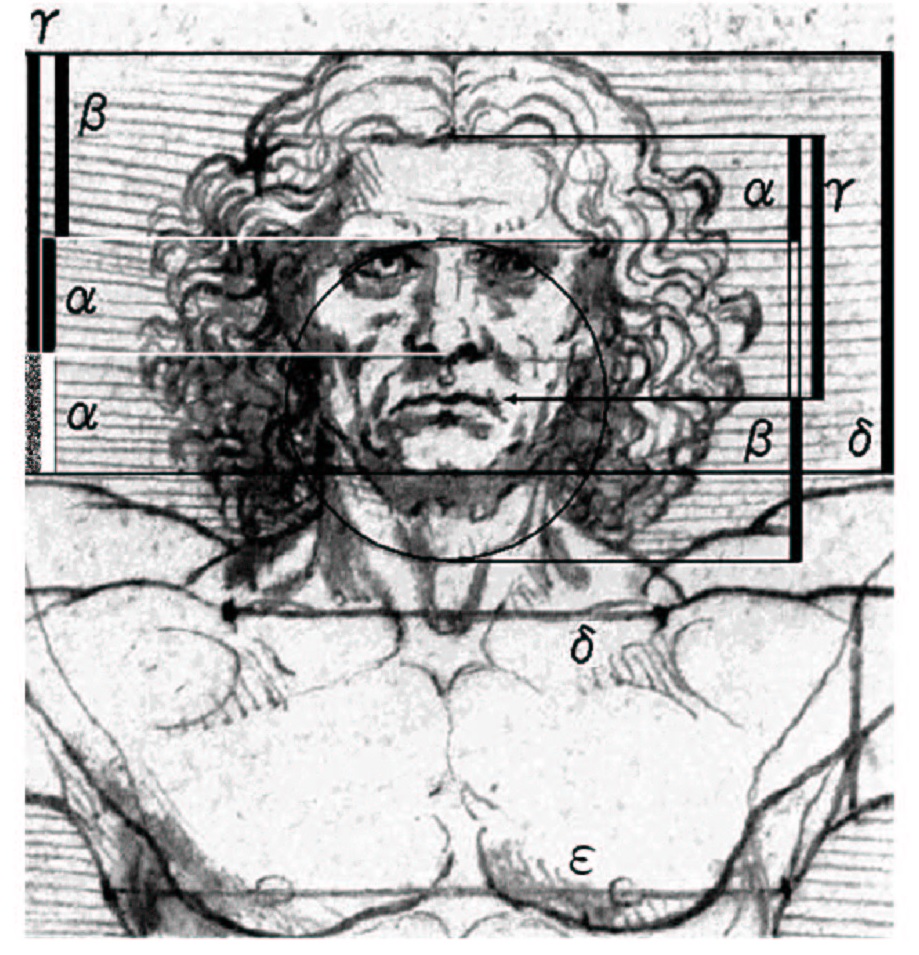

“Harmonic proportion” and “divina proportione” described by Leonardo are examined, being taken up from Windsor folio 12601 (Fig. Ⅲ(1)-1) in the “Corpus of the anatomical studies in the Collection of Her Majesty the Queen at Windsor Castle” in the Windsor Royal Library and folio No. 236 (Fig. Ⅲ(1)-3,4) in the Accademia Gallery of Venice. In the documents of these figures, the dimensions of each part of the head and face are described in detail. Windsor folio 12601 (Fig. Ⅲ(1)-1) is estimated to have been painted approximately between 1488 and 1490, according to Leonardo researchers like Pedretti and etc. As for the folio No.236 (Fig. Ⅲ(1) – 3, 4) of the Accademia Gallery of Venice, Giovanna Nepi Siré stated a new theory that the sketch at the bottom of the right side of folio No.236 had been added by Leonardo as the idea of ”Battle of Anghiari” at a later date around 1503.

It is presumed that Leonardo’s theory of human proportion was summarized in the “Sforza painting theory” of the Milan era, but it is now lost. Windsor folio 12601, the folio No.236 (Fig.Ⅲ(1)-3, 4) and Leonardo’s “Vitruvian Man” of the folio No.228 of the Accademia Gallery of Venice (Fig.Ⅱ(1) – 1) are valuable originals.

Giuseppe Favaro made a detailed examination of the head. Table 2 shows the relationship of the golden ratio, and the sequence of the ratio of the part of head drawn by Leonardo is clearly Fibonacci sequence {1,2,3,5,8,13,…} as shown by italic numbers in the table.

Since the Fibonacci sequence converges to the golden ratio, it can be said that Leonardo made the facial composition along the golden ratio.

Table 2 Position of the part of face examined by Favaro

――――――――――――――――――――――――――――

upper part of mouth 1 : from the lower part of nose to the touch point of lips

chin 2 : from the pit under mouth to the lower part of chin

scalp 2(3) : from the top of head to the hair line

upper part of mouth 3 : from the touch point of lips to the chin (lower part)

forehead 4 : from the hair line to the eyebrow

nose 4 : from the middle point of forehead to the lower part of nose

nose and upper part 5 : from the middle point of forehead to the touch of mouth point of lips

neck 6 : from the lower part of chin to the pit of neck

forehead and nose 8 : from the lower part of nose to the hair line

nose, mouth and chin 8 : from the middle point of forehead to the chin

chin and neck 8 : from the lower part of chin to the pit of neck

eye and neck 13 : from the edge of eye to the pit of neck head height 15(16)* : from the top of head to the lower part of chin

――――――――――――――――――――――――――――

The mark * shows the numerical value of head height of folio No.228 of the Accademia Gallery

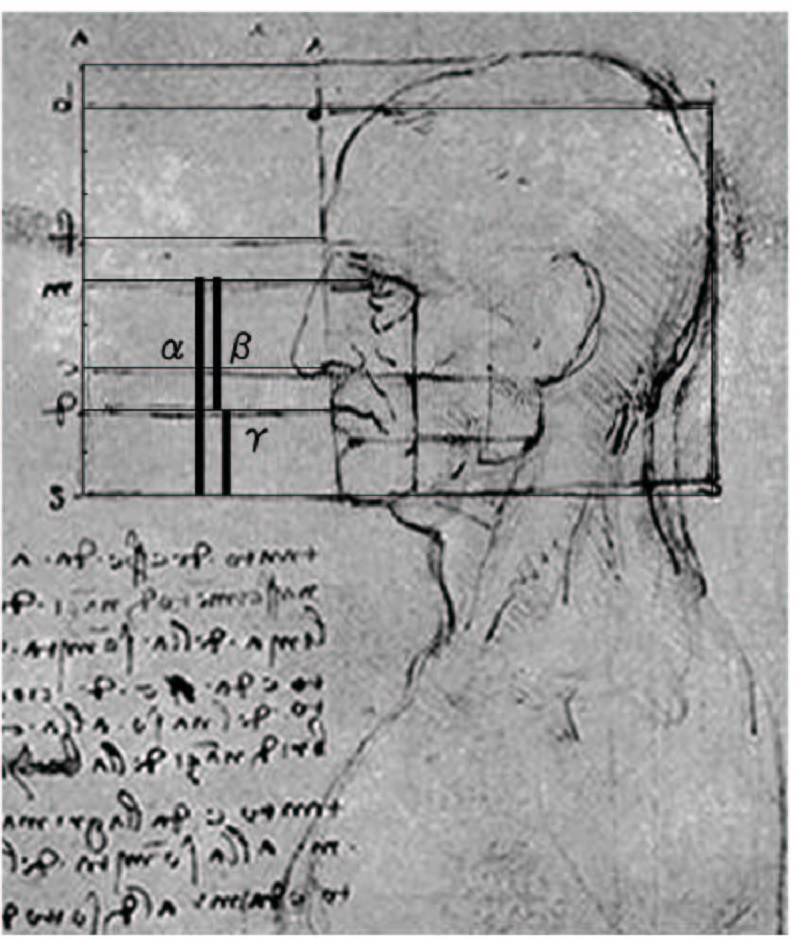

As shown in Fig. Ⅲ(1)-6, α, β, γ, and δ form a geometric progression of the golden ratio.

In Paragone, “things that form a harmonic roportion” compose “divina proportione at the same time united as a whole” (15r), and “the beauty only exists in what forms divina proportione” (18r). Leonardo also declared that the ratio of beautiful appearances clearly exists in what forms divina proportione and harmonic proportion as well (11v-12r) and used “divina proportione” as golden ratio.

As seen in Section 1 of Chapter 2, according to Dr. Mukaikawa’s research, the linear recurrent sequence { 2, 5, 7, 12, 19 …} with 2 and 5 as the initial terms in Leonardo’s “Vitruvian Man” (Fig.Ⅱ(1)-7) was used instead of Fibonacci sequence, which is why Favaro’s work includes ratios other than Fibonacci sequence. When drawing “Vitruvian Man”, Leonardo used a geometric progression of the golden ratio to determine the reference lines of parts of the body (Fig.Ⅲ(1)-8). Therefore, Favaro’s work and Leonardo’s use of geometric progressions of the golden ratio in “Vitruvian Man” are in good agreement.

In Fig. Ⅲ(1)-7, the ratios of α, β, and γ are geometric progression of the golden ratio even though there are some errors. Therefore, it can be said that in this Windsor folio 12601 they were also drawn using “divina proportione”, that is, the golden ratio. In Table 3, it can be said that Leonardo showed the ratios of each part of the head by approximate numbers, although they were actually irrational numbers.

Table 3 Windsor folio 12601 (ratios in unit of 1/10 of head height)

―――――――――――――――――――――――――――― ――― ―――

scalp 1

forehead 3

nose ; from the middle point of forehead

to the lower part of nose 3

upper part of mouth 1

from mouth to upper part of chin 2 ―――――――――――――――――――――――――――― ――― ――― total 10

The geometric progression of the golden ratio found in each part of the body of Leonardo’s “Vitruvian Man” is also shown in the reference lines showing the ratio of the heads of Windsor 12601 and folio No.236 of the Accademia Gallery of Venice.

Dr. Kemp pointed out traces of a compass in Leonardo’s “Vitruvian Man”, but these compass traces were necessary to draw the geometric progression of the golden ratio in this figure.

Similar to Windsor folio 12601 and Academia folio No. 236, Leonardo’s “Vitruvian Man” has compass trace on the tip of the lip, which shows that it was a reference point for determining each ratio of the parts of head. This can be confirmed by the fact that when a circle with the length from the tip of the lip to the eyebrow as the radius is drawn, the arc left on the neck coincides with this circle. Assuming that the length of this radius is β, then α, β, γ, δ, and ε form each term of the geometric progression of the golden ratio, and the length of δ coincides with the head height (Fig. III(1)-8).

Table 4 Position of linear recurrent sequence (italics) in Leonardo’s “Vitruvian Man”

―――――――――――――――――――――――――――――――――

forehead, nose, from upper part of mouth to chin α : ( 1/3 of the face) 4

from upper lip tip to eyebrow β : ( 1/2 of the face) 5

from center of lip to hair line ; from top of head

to bottom of nose γ: (——–) 9, 10, 11*

from chin to top of head ; length of reference line

at top of breast δ : (head height) 14, 15*

length of reference line at nipple ε : δ ×1.618… ——–

―――――――――――――――――――――――――――――――――

The numbers in parentheses are the values in the document, and the marks * are the values of the scalp of folio No.236 of Accademia Gallery of Venice.

Although Dr. Kemp did not pointed out, in addition to the tips of the lips on the above two folios, there are two lines shown by δ and ε forming the golden ratio on Leonardo’s “Vitruvian Man”. However Leonardo did not mention anything about these two line segments in the document of his “Vitruvian Man”.

However these lengths in table 4 were treated systematically as a criterion of proportionality of each part of the body because the length of reference line at the upper end of the chest is equal to the length δ of the head and the reference line ε at the height of the nipple indicates the width of the trunk. Therefore, it should be considered that the compass marks pointed out by Dr. Kemp were not added to contrast with other drawings, but were consciously used by Leonardo in accordance with the proportional system of “Vitruvian Man”. The size of each part of the head and chest of “Vitruvian Man” is as shown in Table 4 above when compared with the figures of Favaro, so the ratio of each part of the head shown in italic {4, 5, 9, 14…} is also a linear recurrent sequence with the first term {4,5}, the limit value of which converges to the golden ratio as the same as Fibonacci sequence.

Problem of production time

Regarding the production date, according to the established theory, Leonardo’s “Vitruvian Man” of the collection of the Accademia Gallery of Venice is around 1490 to 1992, and the Accademia Gallery folio No. 236 is said to be around 1490 in the general theory. It is estimated that Windsor folio 12601 was a sketch from 1488 to 1990.

According to “harmonic proportion” and “divina proportione” that exist in the beautiful appearance written in Paragone it is understood that the golden ratio was considered for the proportional relationship of the head.

Leonardo argued that “harmonic proportion” and “divina proportione” lead to a beautiful appearance in the 28th section of McMahon version of Paragone, “King Matthias’ answer to the poet who disputed with a painter”. And since the period of King Matthias’ life (died in April 1490) and the period of early human proportional research including Windsor folio 12601 overlap, and if this passage reflects the “duel of learning” (duello) at the end of the 1480s, it should indicate that Leonardo used the word “divina proportione” as a golden ratio even before he met Luca Pacioli, who came to Milan in 1496.

Leonardo’s Paragone treats painting as an academic discipline and the painting namely “scienza della pittura” was based on the quadrivium (liberal arts : arithmetic, geometry, astronomy, music). As Ms. Irma Richter pointed out, this shows how Leonardo confronted the tradition of free arts of the Middle Ages. We can understand from Paragone that Leonardo sought scholarly ground in mathematical proportion that visually reproduced nature considering the characteristic “virtò” of painting as the second nature through the comparative debate that were often carried in the court of Milan in the 1480s.

Leonardo shows that he was fighting to establish “painting” as a discipline based on the leading technology of the time, perspective and Vitruvius’ theory of human proportions.

According to Dr. Mukaikawa’s examination, these (1) Accademia folio 236, (2) Windsor folio 12601, (3) Accademia folio 236 back, and (4) “Vitruvian Man” were drawn in this numerical order. Therefore, the arc left on the neck of “Vitruvian Man” (Fig. III(1)-8) is also presumed to be a trace of Leonardo’s examination.

Dr. Mukaikawa estimates them as follows. Accademia folio 236 is the earliest work, and it is probably a drawing belonging to the early anatomical research around 1485 to 1989 being supposed as before, but it is thought that the drawing time is different from that of the reverse side. Secondly Windsor folio 12601 is in line with the time generally believed, because of being in direct contrast to the folio 12637, at the same time as the anatomical study Windsor folio 19059 in 1489. As in the previous chapter, “Vitruvian Man” was after Anghiari period in 1500s, so it is certain that the reverse side of the Accademia folio 236 was before “Vitruvian Man”, and it can be seen that it belongs to Anghiari period.

In the “Corpus of the Anatomical studies” left in Windsor Castle, Leonard wrote, “Don’t let non-mathematicians read my principles” (Windsor 19118v) (Fig. I(1)-5). Heydenreich considered this to be only an anatomical theme, but this statement is of great significance in reexamining Leonardo’s theory of human proportions. Because, even today, only in anatomy the theory of human body proportion is directly related to mathematics, and since Cennini, many “art theories” were written during the Renaissance, but they had a strong character of technology to operate geometry, aiming to imitate and reproduce nature.

Heydenreich’s description of Leonardo’s Windsor folio above can be seen as that related to anatomy and “painting”, including the theory of human proportions. As discussed in this article, Paragone of the Codex Urbino had the problem of “divina proportione”, which was left unexamined mathematically. It would have become clear that ” divina proportione” of Paragone represents the golden ratio, along with the fact that reference lines of “Vitruvian Man” coincide with the geometric progression of the golden ratio. In the description of Paragone, it is told that the combination of “matters consisting harmonic proportion” (l’armonia proportionalità) results in “divina proportione”. And since each of the three drawings taken up here satisfies harmonic proportion and golden division, they can be sufficiently rational descriptions in a mathematical sense.

Both of “harmonic proportion” and “divina proportione” which Pythagoras told exist in each part of the beautiful appearance written in Paragone and Leonardo clearly limited readers of his work to mathematicians. Therefore, since there is no established theory in what is called “my principle”, it was necessary to reconsider the problems of “harmonic proportion” and “divina proportione” together with the Heydenreich’s theory. The description of Paragone shows that the concept of the golden division has existed as a mathematical motif in Leonardo’s “painting” since the end of 1480s.

Section 2 Leonardo’s golden division and “superbipartienti”

Problem of Proportional theory

In Japan, researches were carried on by Professor Shigeru Tsuji and Professor Fumio Shinozuka as perspective research. Medieval European painting existed as a pictorial interpretation of Christian doctrine and did not require linear perspective or human body proportions, but Renaissance artists created works which were equal to those of ancient Greek and Rome on a mathematical basis.

It was these proportional theories that painting, the second nature, created by human hands, needed to transform the three-dimensional quantitative relationship of the object on a two-dimensional picture screen.

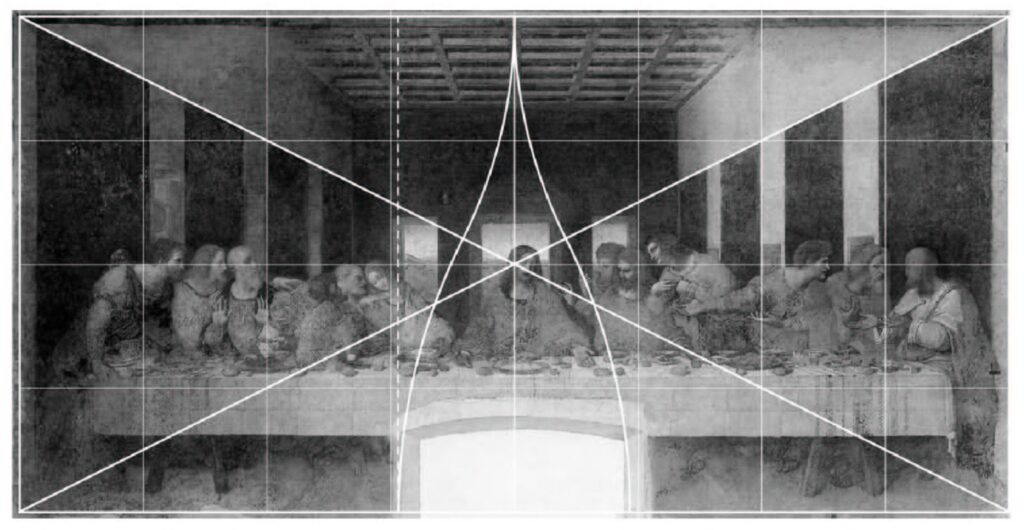

There are various interpretations of Leonardo’s linear perspective, and many interpretations of the room of the “Last Supper”, and the difference is thought because the great painter followed “construzione legittema” (orthodox drawing method) of the Renaissance.

Luca Pacioli’s “De Devina Proportione” has been the first to address the issue of the golden division in a proposition that defines the proportions inherent in a work of art. However, as we saw in the previous section, Leonardo’s theory of human body proportions showed a geometric progression of the golden ratio. In addition, the word “divina proportione” in Paragone, which corresponds to the preface of Leonardo’s “Theory of Painting”, is confirmed to indicate the golden ratio.

Here, in a chronological examination of proportional theory, we picked up what Alberti described as “costruzione illegittema” (wrong drawing method), which was an indicator of the developing stage, and Leonardo’s linear perspective used in the “Last Supper”. Dr. Mukaikawa would like to prepare to examine the time of establishment and the order of the drawing system of Leonardo’s linear perspective.

Golden division and outer division

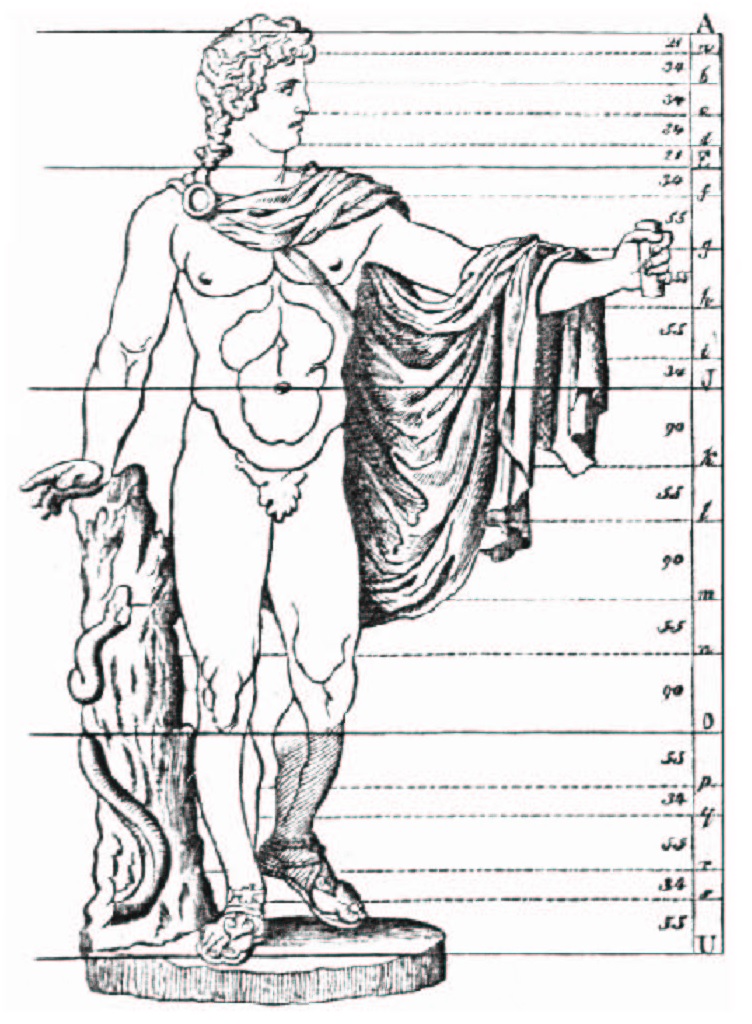

The golden division is a popular term used by the German aesthetician Zeizing in the mid-19th century to indicate the proportions of body parts in ancient Greek sculpture, and has been used as a mathematical term in Germany since the early 19th century (Figure Ⅲ(2)-3). This term was first used in a mathematics textbook by Martin Ohm, the younger brother of physicist Georg Ohm, who is famous for “Ohm’s Law,” and is a relatively new mathematical term.

Dan Brown’s “Da Vinci Code” was published in 2003, highlighting the secrets of his work. In Japan as well, there is a renewed interest in Leonardo’s works, drawings and manuscripts.

Leonardo’s code here refers to the musical harmonized body division based on the description of the ancient Roman architect Vitruvius. The explanation of human proportions found in Dan Brown’s novel commentary books, etc., hardly explains how Leonardo treated the golden division, and also contains some mistakes.

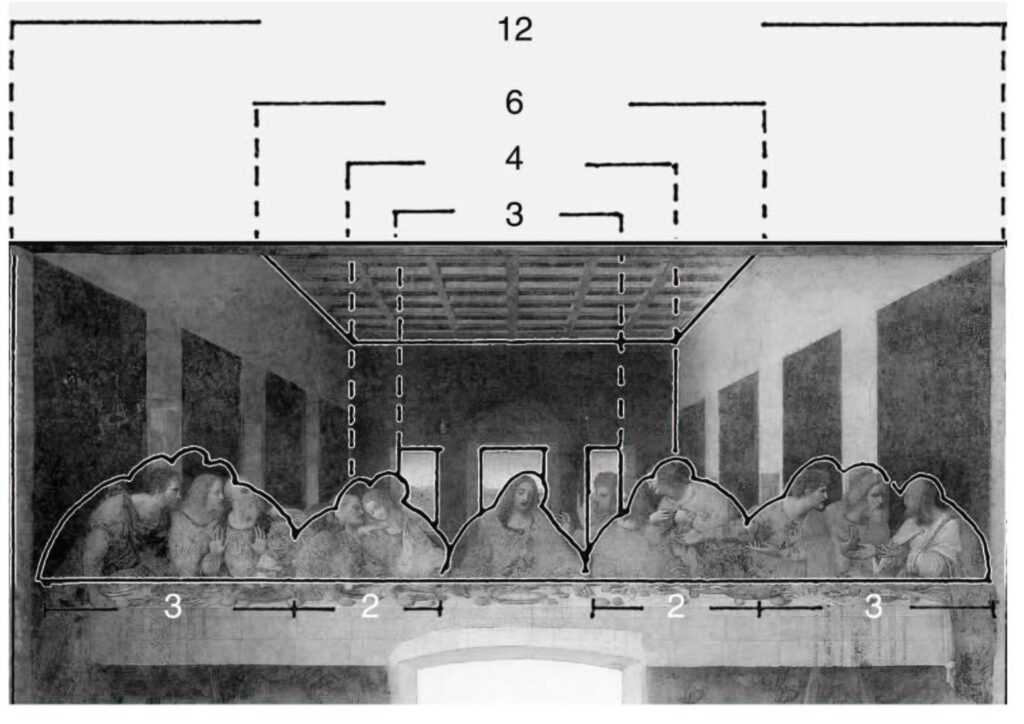

As you can see in Dr. Mukaigawa’s analysis, the drawing of the golden division is used to determine the placement of these apostles on the screen of the “Last Supper”. Not only is the person named Maria Magdalena located at the position divided into 3 to 5 by the square module that divides the image width into eight equal parts, but also the tip of Tomaso’s finger which points to the heaven on the right side near Christ locates at the point where the horizon passing through the vanishing point of Christ’s right temple intersects the arc line for drawing the golden division (Fig Ⅲ(2)-4).

The golden ratio found in the composition of the “Last Supper” was first published in the treatise by Thomas Brachart in 1971, but the point was merely mentioned in the part that touched on musical harmonic proportions, and the problem itself was not recognized (Fig.Ⅲ(2)-5). However, Brachart’s point of musical harmonic proportions is legitimate and is the basis for examining the composition of the interior space of room of Leonardo’s “Last Supper”.

Therefore, let us take up the problem of the golden ratio and its geometric progression that extend Leonardo’s theory of human body proportion and the linear perspective of the “Last Supper”. This problem is an important concept in the art history. It will be explained that the mathematical concept “superbipartienti” that reflects the linear perspective of Brunelleschi’s era and that had not been accurately interpreted in the past, that is, “construzione illegittema” (wrong drawing method) described by Alberti means the golden ratio.

Golden ratio in Renaissance

As already mentioned, in Paragone, the preface of Leonardo’s “Theory of Painting”, written in the early 1490s, it became clear the previously undefined word “divina proportione” indicates the golden ratio. This description is presumed to have been written before Leonardo met Pacioli, suggesting that the golden ratio was known among Florentine artists even before Pacioli’s “De Devina Proportione “.

In addition, Platon’s regular polyhedron in Luca Pacioli’s book “De Devina Proportione” uses figures drawn by Leonardo, which is also proof that Leonardo knew the golden ratio.

The golden ratio is described in Euclid’s “Elements”. However, it is unlikely that this book was read by Italian artists and their apprentices at that time Renaissance. Moreover, at the time, there was no expression of irrational numbers, and even if the golden ratio was mentioned in Euclid’s “Elements”, there was no proper way to express it mathematically.

So how was it expressed ?

Leon Battista Alberti’s book “About Painting”, which might have been known to artists and related craftsmen, has the unclear word “superbipartienti”. If it indicates the golden ratio, it provides literal evidence that the golden ratio was known before the era of Leonardo.

Dr. Mukaikawa says that it means “outer division” from the word element analysis of “superbipartienti”.

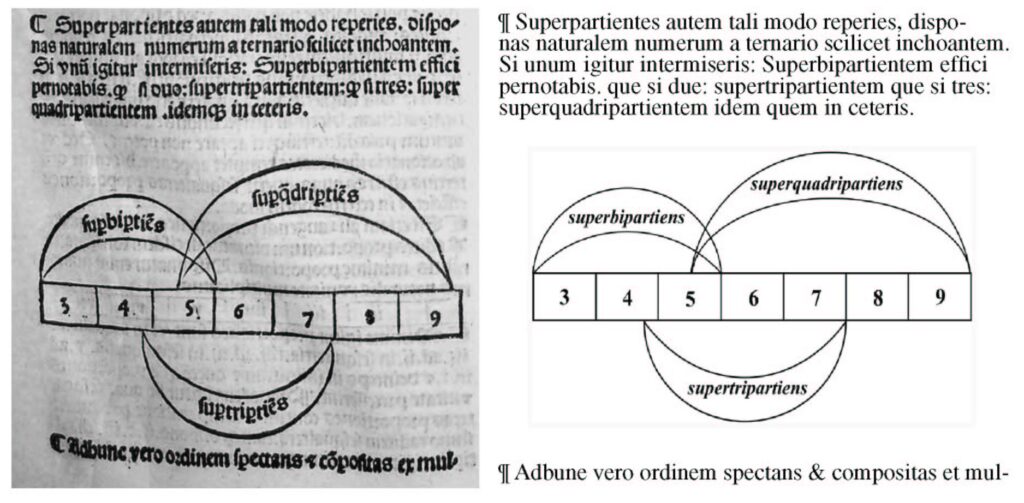

This word is found in “De Musica ” of Boethius’ “Opera (Matematicae et Musicae) ” published in 1491-2. Boethius’ ” De Musica “ played the role of the original text that conveys Pythagoras’ music theory, which was not directly conveyed from the Middle Ages to the Renaissance. It is considered to be the academic source of “superbipartienti” used by Alberti and Leonardo who used this word in the “Last Supper”.

From the relationship between the pitch of the Pythagorean musical scale and the harmonic proportion, the problem of the length that separates the string of a single string instrument is discussed in terms of number and quantity. This illustration of the outer division (Fig. Ⅲ(2)-10) is explained from the Pythagorean scale theory, and shows that the scale can be obtained by dividing the string length by a simple integer ratio.

In fact, this mathematical concept seemed to be difficult for Leonardo as well, and the word “superbipartienti” is found from the reverse of the 48th folio to the front of the 50th of Codex Madrid II, which was in Alberti’s description of ” construzione illegittema” (wrong drawing method). It also corresponds to the inability for Leonardo not to handle irrational numbers as he wrote in Codex Atlantico folio 331r, which is thought to be written around 1504, “ask Luca Pacioli about root multiplication”.

As Professor Susowake pointed out, “superbipartienti” can be thought as being known as two-thirds among the Florentine painters of the time.